When Premier Brian Pallister talks about his desire to see Manitoba public-sector workers shoulder more of the economic burden of the COVID-19 pandemic, he usually employs a family analogy.

“When members of your family are hurting, you don’t turn around and walk away. You do your part to support them and help them,” Pallister said Wednesday, as he has several times over the past seven weeks.

“That’s what the people in the private sector need from us right now. They need our encouragement and support.”

To the premier, this “encouragement and support” appears to translate into some public-sector employees working fewer hours or not working at all.

This premier has portrayed this as a matter of fairness.

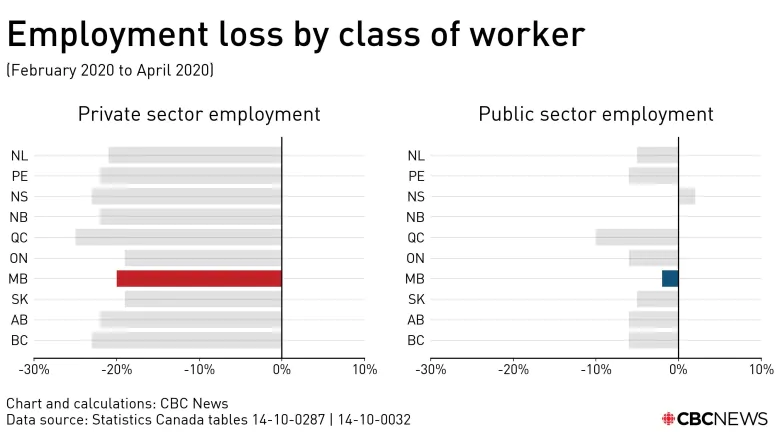

Between the start of Canadian leg of the pandemic and the middle of April, when Statistics Canada conducted its latest labour survey, 77,800 private-sector jobs were lost in Manitoba.

By comparison, only 3,500 public-sector workers lost their jobs.

The disparity seems obvious, in terms of numbers. But there is very little equivalence between most of the private-sector jobs that were lost and the public-sector jobs Pallister wants to see clawed back, temporarily or otherwise.

Manitobans aged 15 to 24 accounted for 35 per cent of the job losses. Manitobans working in the hospitality, retail and wholesale sectors accounted for 44 per cent of the newly unemployed.

In other words, the pandemic has largely thrown the most vulnerable Manitobans out of work. That is, people earning the lowest wages, often at part-time hours.

By and large, the public-sector jobs Pallister wishes to downsize pay far better and offer more benefits to their employees.

Once again, the premier may very well see this disparity as a situation that ought to be corrected.

It may not jibe with his family analogy — few families get stronger when more of their members are ailing from one malady or another — but it is safe to suggest the Progressive Conservative leader comes by an ideological opposition to the idea of larger government and public-sector unions rather honestly.

As economists and business leaders have pointed out repeatedly, it’s unclear how removing more people from the public payroll benefits the private sector. The more people who are able to spend money during a recession, the greater the total purchasing power within the province.

The premier has appeared to struggle to explain this fiscal logic. He also has yet to elucidate the rationale for spending $45 million on seniors, indiscriminate of their wealth or income, along with another $120 million on front-line workers who have remained employed throughout the pandemic.

It is valid to ask whether another form of logic is at work.

In April, when most provincial departments, Crown corporations and other provincially funded entities were asked to prepare workforce-reduction scenarios, the Treasury Board Secretariat asked all those potential targets to think about the concept of something called Government 2.0.

“How will all organizations emerge post-COVID-19 as more agile and relevant parts of government?” the Treasury Board Secretariat asked of the Crowns, universities, boards and other entities in a PowerPoint presentation.

“The world will have changed forever — how will your own organization?”

It may have seemed the Pallister government was using the pandemic as a pretext to reshape the provincial government into something leaner and perhaps meaner.

At the time, Finance Minister Scott Fielding, who is responsible for the Treasury Board Secretariat, dismissed the ideas the PCs are trying to radically reshape the province. He went as far as calling Government 2.0 a “throwaway line” in the presentation.

Since then, Manitoba Hydro has been instructed to shed hundreds of jobs even though the province appears to have no means of squeezing more money out of the Crown corporation and spending it on, say, protective equipment for health-care workers.

As well, the University of Winnipeg and the University of Manitoba have been handed reduced grants at a time when more young Manitobans are not working and are available to take courses.

The U of M budget cut is $17.3 million, which works out to five per cent of its provincial operating grant.

Pallister justified the move Wednesday on the basis the university faces reduced costs at the moment, as opposed to increased demands.

“There are cafeterias that aren’t serving food. There are trips that don’t need to be taken. There are conferences that don’t need to be attended. There is money to be saved,” he said.

The university, however, says it’s suffering from a drop in private donations — wealthy donors are not in the best position to give right now — while other forms of revenue have disappeared.

“Our budget may have to be reduced even farther as we see a drop in revenue,” U of M vice-president John Kearsey said Wednesday, referring to parking, recreation, catering and conference fees.

“We’re experiencing some of the same losses in revenue as communities are experiencing, so we’re going to have to make up the difference there as well.”

Pallister described the cut to the U of M budget as temporary. U of M president David Barnard contradicted the premier, informing staff that one percentage point of the five-per-cent cut — $3.5 million — is an “ongoing,” or permanent cut.

Thanks to inflation, even flat funding is a de facto budget cut. Fielding’s insistence in April that the province is not using the pandemic as a pretext to cut universities has been contradicted by the budget-cut directive issued by Economic Development and Training Minister Ralph Eichler.

On top of that, Pallister has signalled his intention to further retool post-secondary institutions into training organizations, as opposed to places of higher learning.

On Wednesday, the premier announced the formation of new economic advisory body whose duties include “a further alignment of post-secondary programs and courses with the province’s labour market needs and priorities.”

“This is maybe the most chilling thing. The budget cuts are terrible, but this actually might be the bigger long-term problem,” said Scott Forbes, president of the Manitoba Organization of Faculty Associations.

Forbes, a University of Winnipeg biologist, argues Pallister lacks the authority to make such a change.

“There’s legislation on the books which which dictates that universities are autonomous organizations and they govern what programs they offer,” Forbes said.

“Now he’s he’s put together a board — which includes no university representatives — to tell post-secondary institutions how they’re supposed to run their programs to better align with the economic goals of the province?”

In April, Fielding dismissed the idea the Progressive Conservative government is using the pandemic as a pretext to reduce the power of ideological opponents in the public-sector unions and academia.

“We’re not looking at this [on] an ideological basis,” the finance minister said of cuts that were only theoretical at the time.

“We’re looking at this to see if there’s some savings that can be dedicated towards protecting Manitobans and that’s what that exercise is all about.”

It may be months before Manitobans get a peek at the provincial books to see how much money was spent on health care during the first few weeks of the pandemic. At that point, Fielding will either be vindicated or found wanting.

In the meantime, Manitobans will get to see whether the family Pallister envisioned turns out to be The Brady Bunch or the Lannisters from Game of Thrones.

![[Book Review] The Blade Itself (The First Law Trilogy) by Joe Abercrombie](https://bendthekneegot.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/01/1516047103_maxresdefault-218x150.jpg)