Fueled by endless cups of coffee, French author Honoré de Balzac produced more than 90 novels and short stories peopled by 2,400-plus characters during his lifetime (1799-1850).

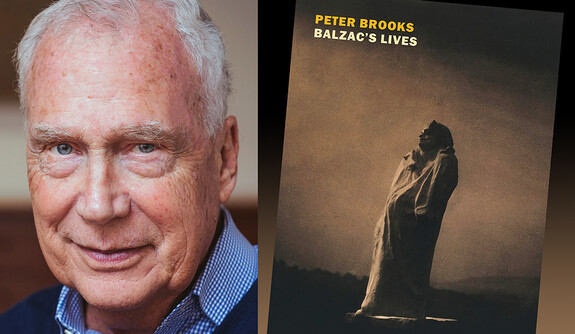

“Balzac’s Lives,” a new book by Yale professor Peter Brooks, presents biographies of nine of these characters — among them a money lender who calls himself a poet, a colonel believed killed in battle who returns to re-claim his old life, a writer who thinks he can enter into others’ bodies and souls, and a man (Eugène de Rastignac) whose name in France even today is synonymous with an ambitious and unscrupulous person. Brooks calls “Balzac’s Lives” an “antibiography.”

Brooks, Sterling Professor Emeritus of Comparative Literature in the Faculty of Arts and Sciences, returned to campus last year, having taught at Princeton since his retirement from Yale in 2009. This spring he will teach (with Jane Tylus, professor of comparative literature and Italian) a graduate seminar called “Novels of War, Revolution, and Plague,” about novels that try to deal with major historical events and their impact on the lives of their fictional characters.

The following conversation has been edited and condensed.

You’ve introduced generations of Yale students to Balzac’s writings, and you’ve edited translations of his works. What inspired you to write an “antibiography” about him?

I’ve been wanting to write a book about Balzac for some 30 years, but I didn’t know how to go about it. There are already some good biographies. So I thought: What if I did biographies of his fictional characters? — because they are extraordinary. Together they create the dynamic of a fully furnished world, which is a kind of critical mirror held up to the France of his time. I think they speak to Balzac’s inner life, his obsessional life, more than to his external life. So that’s what I did, and I had a lot of fun doing it.

You say Balzac’s “The Human Comedy” is like “the Office of the Census. But much more fun.” How so?

Once he decided that all his novels were going to be linked together into this sort of super-novel called “The Human Comedy,” Balzac actually said, “The writer of it is French society. I’m nothing but the secretary.” Well, that’s crazy, but it leads to the notion that he always has to write more because he has to cover all social strata, all walks of life, all sexual proclivities and orientations, politics, everything. So it becomes a very crowded world. It’s a world of dramatic choices and heightened emotions, including the problem of finding out who everybody is. As we move from one novel to the other, we meet a lot of old friends and begin to see the contours of a whole world.

I think the only thing comparable for us today is something like “Game of Thrones.” If you start binging on “The Human Comedy,” it’s very much like binging on a TV series that you can’t stop.

What do you mean when you write: “Sex is for Balzac the riddle of the sphinx …”?

Balzac’s characters are usually interested in and often obsessed with sex. Yet what sex means for Balzac is never quite clear. He often sees sexuality as alluring but dangerous, and he writes about some very extreme cases. There’s a story of a soldier lost in the desert in Egypt during Napoleon’s campaigns who goes to an oasis where he finds he’s sharing a cave with a panther, and then develops a kind of love relationship with the panther. It’s very erotic; it’s scary also. I think it’s a way for Balzac to talk about a man’s understanding of female sexuality without quite being overt about it. It’s an amazing story — which ends badly.

Balzac had a very fluid sexuality. Some biographies have suggested that he was happier in his relationships with men than with women. He’s happy to think about sexual relationships of all types. It was Freud who called sexuality the riddle of the sphinx, and I think it is for Balzac also. He never solved it.

Balzac would rise at 9 p.m. and write through the night, wearing a monk’s robe, and drinking “innumerable” cups of coffee. Do you have any writing rituals?

I’m just the opposite. If I don’t start writing early in the morning right after a quick breakfast, I’ll never get to it. I can only write in the morning hours; by afternoon, new ideas don’t come. I can revise what I’ve written but not come up with anything new and creative.

Balzac’s practice really was self-destructive: He died at age 50. But he needed the silence, the quiet of the night, to get things done. He had a very active social life and commercial life during the day; he was always running around to editors, wondering where the next franc was coming from. At night he could get peace and close everything else down.

![[Book Review] The Blade Itself (The First Law Trilogy) by Joe Abercrombie](https://bendthekneegot.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/01/1516047103_maxresdefault-218x150.jpg)