Pick-up trucks carrying fighters from Libya’s Brothers Brigade speed along sandy roads, past the carcasses of burnt-out cars, shuttered shops and wrecked buildings, their empty shells disfigured with the ugly pockmarks of battle.

On reaching the frontline, the men take cover in homes long abandoned, as sporadic bursts of gunfire echo across a once bustling neighbourhood of Tripoli that has been transformed by war into a militarised wasteland.

Striding between buildings, Capt Mohammed Mukhtar nods in the direction of enemy fighters, forces loyal to Gen Khalifa Haftar, who are spearheading his assault on the Libyan capital and are hunkered down a few hundred metres to the south-east in yet more deserted buildings of the Ain Zarah suburb.

“It’s been quiet the past few days, but we are worried about what they will do next,” Mukhtar says. “The enemy will try to push into Tripoli again.”

It is not his only concern. Among the ranks on the other side are Russians from the Wagner private security group, including snipers, he says. “They bring Janjaweed [Sudanese mercenaries] and Russians to kill their Libyan brothers. Why do they do that?”

Like many of his countrymen, the 30-year-old fighter is worried about the rising internationalisation of a 10-month conflict in the oil-rich north African nation. Lined up behind Haftar – who controls the east, central and southern areas of the country – are the United Arab Emirates, Egypt and Russia with political backing, at least, from France.

On the other side, Turkey has ramped up its military support for the UN-backed Government of National Accord in Tripoli, for which Mukhtar is fighting.

Proxy war

Many Libyans believe it will be these outside powers that determine whether the fighting ends, amid warnings from diplomats that all the protagonists risk being sucked deeper into a protracted proxy war that threatens to reverberate from the Sahel across north Africa to the Mediterranean.

These developments have already inflamed tensions between Haftar’s backers and Turkey, which is increasingly viewed by Abu Dhabi, Cairo and Riyadh as a destabilising force in the Arab world and supportive of Islamist movements they deem a threat to the region. Libya has become the theatre where these rivalries are playing out to deadly effect on the battlefield.

Libyans offer multiple theories for the outside involvement in their country, from the desire of foreign powers to spread their influence to gaining control or access to Libya’s abundant resources and Mediterranean ports.

“The problem is not [just] Libyan,” says Fathi Bashagha, the country’s interior minister. “It’s 20 per cent Libyan and we can solve this; 80 per cent is from the outside countries involved in Libya.”

The years since the toppling of Muammar Gadafy in 2011 have been characterised by cycles of violence that have created fertile ground for criminal gangs, extremists and human traffickers preying on vulnerable migrants desperate to begin new lives in Europe. At least 2,000 Libyans have been killed and more than 150,000 forced to flee their homes in areas such as Ain Zarah since Haftar launched a surprise assault on Tripoli last April.

The dynamics of the war shifted in January after Turkey deployed troops to Libya, heeding a plea from the besieged Tripoli government as Russian mercenaries and air superiority offered by Chinese-made drones – supplied and allegedly operated by the UAE – appeared to tip the balance in Haftar’s favour.

Ankara parachuted in military advisers, artillery, ammunition and other equipment, Libyans and diplomats say. Crucially, Turkey has provided US-made Hawk air defence systems to cover a stretch of government-controlled territory from Zawiya, west of Tripoli, to Misurata, east of the capital, that appear to have neutralised the threat of the drones.

Forceful intervention

Turkey insists its troops will have no combat role. But Ankara has dispatched Syrian Turkmen militias to Libya, adding yet another foreign ingredient to the mix. Having started to arrive in December, there are estimated to be some 3,000 Syrian fighters in Libya, a foreign diplomat says.

Ankara’s message to Haftar and his backers seemed clear: it would not allow Tripoli to fall. Its forceful intervention triggered a flurry of diplomacy. In January a Russian-Turkish effort to mediate a truce between Haftar and Fayez al-Sarraj, prime minister of the Tripoli-based government, was launched. But it floundered when Haftar left Moscow without signing a deal.

But the sight of Moscow and Ankara taking the initiative seemed to jolt western powers into action. Days later, Germany hosted a conference in Berlin attended by European leaders and the foreign powers involved in the conflict. The gathering called for a halt to the hostilities and an end to foreign interference. Instead, more weapons poured into Libya, with foreign players arming their proxies to curb their regional rivals’ influence.

António Guterres, the UN secretary-general, in February described what is happening in Libya as “a scandal”. His envoy, Ghassan Salame, said both sides in the Libyan conflict had “benefited from new arrivals of weapons, new kinds of weapons and ammunition and also from the arrival of new recruits or new foreign fighters”.

The UN is still pushing ahead with diplomatic efforts and a Joint Military Commission, made up of officers from the rival Libyan factions, met this month. But given the failure of past initiatives, the arms build-up, the bitter mistrust between the sides and Haftar’s history of disdain for diplomacy, few in Tripoli were betting on a swift resolution.

Last week, the Tripoli government suspended talks after Haftar’s forces shelled the capital’s only functioning airport, killing three people.

“Haftar cannot stop the war because his project is to rule by tank and artillery,” says Bashagha. “This is a big investment for Haftar and the [United Arab] Emirates, it’s impossible for them to stop the war.”

The Turkish support has also emboldened factions loyal to the Sarraj government, meaning they now appear less willing to negotiate.

“Now [Haftar] doesn’t control the air I think we are moving shortly from a defensive phase to an attack phase. At the same time, we are insisting on a political solution that doesn’t include Haftar,” says Khalid al-Mishri, head of the High Council of State, an advisory body to the Tripoli administration. “Sarraj started weak; now he’s much better. He’s learned from time. Before he trusted Haftar; now he doesn’t.”

Palpable frustration

In downtown Tripoli, life proceeds with a semblance of normality. Supermarket shelves are well stocked and cafés and restaurants enjoy steady trade as generous state subsidies and a civil service that employs more than 1.8 million of the country’s 6.5 million people have cushioned the conflict’s economic damage.

But Haftar-loyalists have blocked Libya’s oil exports – the country’s lifeline – since the eve of the Berlin meeting, meaning the economic situation could rapidly deteriorate. It has already cost the country more than $2.1 billion (€1.9 billion) in lost revenue, according to official data.

The frustration of Libyans is palpable.

“We need a strong government, but it’s weak. Now everything is broken, we are starting from zero again,” says Malik, a health official, sitting in a sandbag-protected corner of a field hospital set up in a warehouse packed with nappies. “It’s a Game of Thrones, everybody in Libya wants the chair. Money, guns and oil – it’s like the mafia.”

The field hospital is in one of the many southern Tripoli neighbourhoods that abut front lines where people live with the daily threat of rocket fire. Homes, factories and shops, along with the airport, have been hit by Haftar’s forces.

“You can see for yourself those are normal cars in the street. Why do they attack us?” asks Mohammed al-Daas, hours after his family of six was woken by the blast of a rocket striking their home. As he and neighbours inspect the damage – shattered windows and broken tiles inside; destroyed cars and walls scarred by shrapnel in the narrow street outside – they vent their anger at Haftar and the foreign powers.

“People living with this situation can do nothing. We are just scared of the bombs,” says Juma, a neighbour. “In Berlin, they could have stopped this but … France doesn’t want to stop it, the UAE doesn’t want to stop it.”

Regional powers

Many trace the foreign interference to Nato’s support for the rebels who toppled Gadafy and then, in the eyes of many Libyans, left them with a state hollowed out by more than four decades of dictatorship to their own fate.

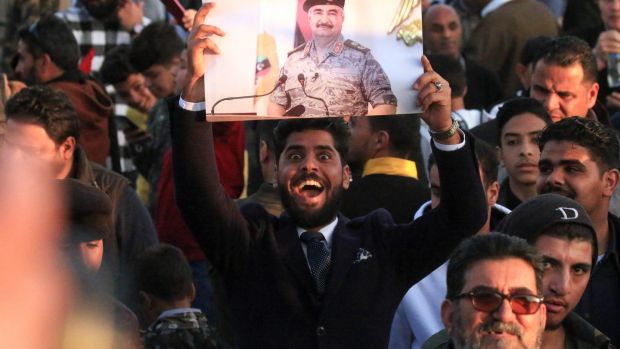

As chaos reigned and Libyan factions carved the country into a patchwork of fiefdoms, regional powers backed rival sides. That escalated after failed elections in 2014 deepened the divisions. Haftar and his self-styled Libyan National Army launched a campaign in the east against pro-Islamist militias in Benghazi and other cities.

In the following years, the one-time Gadafy-loyalist-turned-CIA-asset improved security in the east and championed himself as the man spearheading the fight against Islamist extremists. The narrative struck a chord with his supporters, notably Egypt, the UAE and France, even as his critics describe the 76-year-old as a ruthless, stubborn leader in the mould of Gadafy.

Officials in Tripoli are willing to accept that Egypt has legitimate concerns about its unstable neighbour. But the support Haftar enjoys also reflects the penchant Arab regimes have for backing strongmen, often in the name of quashing Islamist movements and promoting “regional stability”.

For the UAE, it is one of the most geographically distant examples of the assertive foreign policy Abu Dhabi adopted in the wake of the 2011 Arab uprisings. The role of Russia, which had strong relations with Gadafy’s regime, is another sign of the Kremlin seeking to exert its influence in the region. Moscow has printed billions of Libyan dinars to support Haftar’s finances.

His anti-Islamist narrative also resonated in the White House and the Elysée Palace. When Haftar launched an offensive in the south that precipitated his attack on Tripoli, France publicly supported him. Months later, US-made Javelin missiles, purchased by France, were discovered by government forces after they seized one of Haftar’s camps. “The French, almost to a person in policymaking, see him as the second coming,” says a foreign diplomat.

Arms embargo

US president Donald Trump called Haftar days after he launched the offensive on Tripoli, praising his “role in fighting terrorism and securing Libya’s oil resources”. Washington has criticised the role of Turkey and Russia, but has been conspicuously quiet about repeated arms embargo violations by its Arab allies, the UAE and Egypt.

An Arab official says part of the motivation for those backing Haftar is concerns that “extremists, including the [Islamist political group] Muslim Brotherhood” could gain access to Libya’s oil wealth. “Then we will see its [money] all over the place.”

“We see the other side ramping up and we can’t allow that,” the official says. “We will not allow Turkey to establish a foothold in what is an Arab issue, and we will not accept Turkey tilting the balance in what is a regional [one].”

Libyan officials and diplomats in Tripoli say the interim administration asked Ankara for greater military backing only after the government failed to muster support from European powers and the US. Turkey agreed after securing a maritime agreement with Tripoli to give it access to oil and gas resources in the Mediterranean.

But the costs and risks for Ankara are mounting. President Recep Tayyip Erdogan on Saturday acknowledged for the first time that Turkey had lost soldiers in Libya. “Of course we have [lost] a few martyrs,” he said. “Let’s also say this. In return for those few martyrs, we have neutralised close to 100 mercenaries over there.”

The following day, a spokesman for Haftar’s forces said they had killed 16 Turkish soldiers in recent weeks.

Hotchpotch of militias

Libyan government officials dismiss Haftar’s claims that Tripoli is a hotbed of Islamists and diplomats, arguing that the scale of the extremist threat in the country’s west is overstated.

However, the Sarraj government has struggled for credibility since it was created during UN-brokered talks in 2015. The unelected administration has been beholden to a hotchpotch of militias with little influence outside Tripoli and is blamed for widespread corruption that has enriched militiamen while failing to deliver development.

Mukhtar, who first picked up a gun to fight Gadafy forces in Misurata in 2011, is among those Libyans who feel let down. But, he believes, the country’s domestic woes cannot be solved as long as the foreign weapons pour in. And while he welcomes the arms and ammunition from Turkey, he harbours doubts about the Syrians fighting on his side.

“I’ve been fighting since 2011. I joined the army in 2013 so I’ve been fighting for eight years. Now I need Syrians to fight with me?” he asks. “The international community and the UN said they would help us, but they didn’t.” – Copyright The Financial Times Limited 2020

![[Book Review] The Blade Itself (The First Law Trilogy) by Joe Abercrombie](https://bendthekneegot.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/01/1516047103_maxresdefault-218x150.jpg)