Audiences were horrified when, in the penultimate episode of Game of Thrones, Daenerys Targaryen, a leader often portrayed as a human rights defender, torched a city full of terrified civilians from astride her dragon. It seemed out of character, some said. As a plot point, argued others, it was poorly built up. It ruined a feminist hero. But the underlying reason for the outcry went unspoken: The deliberate targeting of civilians from the air, using incendiary weapons that are impossible to escape, is rightly recognized by Americans as a terrible crime—something good actors just don’t do.

Although it seems obvious that Americans would oppose such war crimes, it was not a historical inevitability. After all, the United States perpetrated some of the most horrifying episodes of aerial firebombing in history and largely with public support. Saturation bombing of civilians in World War II killed, by one scholar’s estimate, around 750,000 civilians—several times the number who died in the nuclear bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki. Babies were burned alive on their mothers’ backs, and whole families suffocated in cellars, but Americans largely shrugged.

So what does HBO’s depiction of a firebombing, and the outrage afterward, tell us about war crimes in the present-day American conscience? Would Americans have been so quick to judge Daenerys if the city hadn’t surrendered before she began her murderous spree? Would Americans be so morally outraged if the United States’ own troops’ lives were on the line? With the Trump administration rumbling about war with Iran just as audiences were gasping over the sack of King’s Landing, these questions are not merely academic.

Back in July 2017, around the time Daenerys first landed at Dragonstone, two political scientists from Stanford University and Dartmouth College published a survey in which they asked 780 Americans exactly this kind of question. Survey respondents were told to imagine whether, in an intractable and bloody war with Iran, they might agree to a Targaryen-style saturation bombing of a populated city—likely to kill 100,000 civilians—in order to induce an Iranian surrender and save the lives of 20,000 U.S. troops. When put this way, two-thirds of respondents leaned toward a “shock” strike against a civilian city over an ongoing and bloody ground war. The authors concluded that “the U.S. public’s support for the principle of noncombatant immunity is shallow and easily overcome by the pressures of war.”

Faced with dragon fire, television audiences did not react as this survey finding would predict. The response has implications far beyond fiction. Because successful TV shows transport audiences to a world that feels realistic, viewers experience that world, and react to it, much the same way they experience reality. Audience reactions to the final arc of Game of Thrones—with a sample size much larger than 780—are perhaps another, perhaps even better indication of how Americans might react to a real-world firebombing today.

Consider major commentaries about the penultimate episode. We did not hear commentators argue that the firebombing of King’s Landing would have been perfectly fine if the city hadn’t surrendered, as Tokyo refused to do before the Hiroshima bombing and as Iran refused to do in the political scientists’ fictional scenario. Nor did we hear that Daenerys should have simply incinerated the city’s civilians while her troops waited safely outside the walls.

Consider also reactions to the show’s finale. The complaints varied, but few argue that Daenerys deserved the throne after what she did— only 11 percent of U.S. viewers still supported her after the sack of King’s Landing. For most viewers, it was not a question of whether the show would punish Daenerys for her crimes but how. That the punishment came from the adopted son of Ned Stark, a man whose last act while in power was sentencing a man to death for massacring civilians, only confirms the point. Despite arguments to the contrary, the show’s key message was that rulers ignore ethical norms at their own peril. Sure, Ned lost his head, and Daenerys lost her mind, but the narrative arc of the story bent ultimately in the direction of justice. Fans complain about much but not about this.

Like survey experiments, pop culture—and audiences’ reaction to it—can be a window into a society’s values. What Game of Thrones has revealed more clearly than any survey is that most Americans care more about fighting wars justly than some political scientists would have us believe. Most of all, Americans care about following the laws of war: Survey experiments show opposition to torture and civilian targeting increase the more information participants are given about international law.

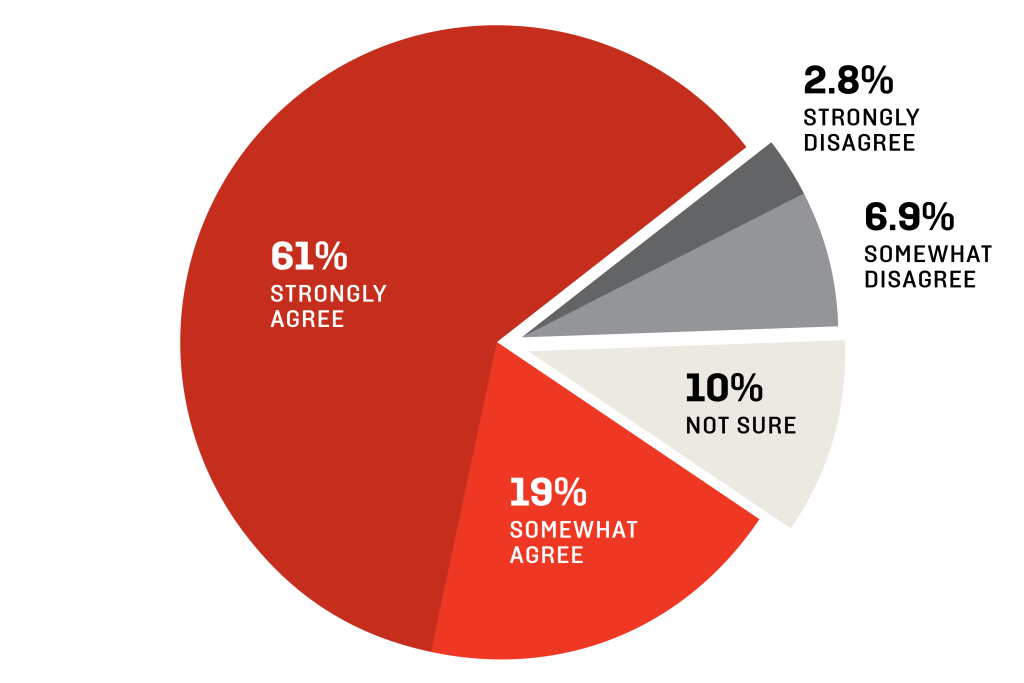

New survey research shows this to be true even of saturation bombing, refuting the Stanford/Dartmouth finding. In a working paper recently presented at the International Studies Association, we asked 2,250 Americans whether or not they agreed with the statement that targeting civilians in war is categorically wrong. Eighty percent “strongly agreed” or “somewhat agreed” with this statement.

Agreement That It’s Wrong to Attack Civilian Populations

Source: Working paper by Charli Carpenter and Alexander H. Montgomery, based on a survey of 2,250 Americans.

Respondents were also asked to explain their answers: Why is it wrong to target civilians? The results were striking. Many of those who strongly agreed that targeting civilians is wrong refused to even answer. They declined to weigh cost-benefit calculations or consider the moral culpability of the civilian population or even invoke such explanations as the Geneva Conventions. “It’s just wrong,” they said in their open-ended comments. Or: “You just can’t.” One wrote: “Why would you even ask such a thing?”When we replicated the earlier Stanford/Dartmouth experiment, but with an open-ended question rather than forcing respondents to choose between two terrible options, we found much more nuanced moral thinking than the original authors. The majority of Americans rejected both the ground war and the strike in the fictional Iran scenario, arguing for other options: precision air power against military targets, diplomacy, or retreat. We found support for the strike went down even further when respondents were informed about international laws and norms or even were asked to just think about ethics—something Game of Thrones constantly invited its viewers to do.Our research confirms the evidence from reactions to the show’s finale. Americans would have wanted Daenerys to use air power but only against military targets such as the Iron Fleet. They would have wanted her to limit its use inside the city walls to avoid collateral damage. They would have wanted her to target the Red Keep, if needed, but not the streets of Flea Bottom. They would have chosen to let boots on the ground do the work of breaching the Red Keep and capturing Cersei Lannister and expected the Unsullied, Dothraki, and Northmen to fight soldiers rather than massacre civilians. All of these arguments show a clear and consistent understanding of, and sensitivity to, the international laws of war.

As such, watching beloved characters turn into war criminals will always be deeply disturbing for American audiences—just as watching the country’s politicians turn U.S. airmen and troops into war criminals or pardon them for terrible crimes is seen by political audiences as a national disgrace. The firebombing of King’s Landing, and viewers’ reaction to it, should be a warning to presidents who want to bring back torture, politicians who speak of carpet-bombing, or others who might contemplate similar “shock and awe” actions in any future war.

![[Book Review] The Blade Itself (The First Law Trilogy) by Joe Abercrombie](https://bendthekneegot.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/01/1516047103_maxresdefault-218x150.jpg)