When the Tour de France came to Dublin, Enniscorthy and Cork in 1998, it was destined to be a celebration of cycling. Instead, it marked the beginning of a series of scandals that led to the world’s most-famous race being dubbed the Tour de Farce or Tour du Dopage.

Just days before the race began in Dublin, a Belgian sports physiotherapist, Willy Voet, was stopped in his Festina team car by customs near the French/Belgian border. What they found rocked professional cycling – large quantities of syringes, EPO, hormones and testosterone. The team was suspended in what became known as the Festina affair, a low in what was one of the darkest periods in the sport’s history. Further scandals followed.

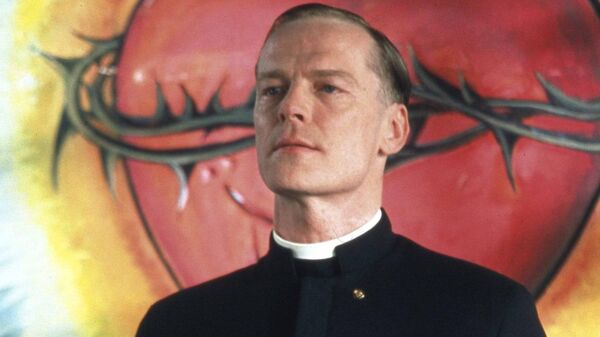

Now a new movie recounts that 1998 tour through the eyes of a cyclist. Though fictional, The Racer shows the dangerous lengths teams will go to for a competitive edge. Shot in Ireland and Belgium, the opening film for the Cork International Film Festival centres on a domestique (support rider) regarded as one of the best in the business. Iain Glen plays the team’s Mr Fixit, the man with the syringes and vials.

“I studied documentaries and a couple of films just to get to know the world it occupied,” he says. “What drew me to the script was it didn’t hold back its punches, I thought it was a very frank and honest, quite a wry, insightful look at a particularly bad period for drug abuse within the sport.

“That tour became known as the Tour de Drugs because of the amount of drugs that were going down at the time. The people within the team and my character, certainly within the context of the film, didn’t have any great qualms about it – everyone was doing it and we were doing it as well. That was the norm. It’s ironic to think that (Lance) Armstrong was about to enjoy his great stretch as being the world-leading cyclist and he won so many tours in a row and this was prior to that. During Armstrong’s time everyone thought the sport had got its act together a bit more.”

Directed by Kieron J Walsh, the movie shows the extraordinary dangers the cyclists face as a result of blood doping. EPO is a hormone that stimulates the red blood cell count, improving performance by increasing oxygen and endurance. But overuse can have serious impacts, slowing the blood flow, thickening the blood and even stopping the heart while users sleep. The same blood-thickening effect can also increase the risk of blood clots, strokes, high blood pressure and heart attacks.

At this time when EPO use was rampant, cyclists would set their heart-rate monitors to sound an alarm if their heart rate fell below a certain level as they slept. In the film, we see cyclists in a near-state of collapse being placed on their bikes in the middle of the night to get their heart rate up. Needless to say, there’s a sense of black humour between the cyclists featured in the film.

“People weren’t wrestling with their consciences as they decided how they could compete at the highest level, they were just doing what everyone did. And I thought that was accurate and telling,” says Glen. “You would have to have a gallows humour.

“The conceit of zoning in on this domestique, someone who had sacrificed his entire life for cycling with the intent of never, ever winning himself, who would put his whole life on hold, and then physically put his own body through the abuse that he did to try and compete, I thought was a very powerful conceit for the film.”

Glen is one of Scotland’s best-known actors, mixing it up between roles in theatre and the big and small screen. But he didn’t initially consider an acting career, stumbling into drama while studying at Aberdeen University.

“It was there that friends of mine got involved and I was slightly dragged against my will into it. I had no idea what actors were and that you could earn a living for what they did.”

That changed when he performed a small part in The Crucible. “I felt that I could occupy that space in my imagination where I believe the world in which I was standing in and seemed to be able to project that in a small way. I just got really addicted very quickly for that feeling. I bumped into it very accidentally, I had no great desire, I didn’t even know what it was until I was 18, really.”

Many of those projects have brought him to Ireland – including playing Jorah Marmont in Game of Thrones.

A movie shot in Ballyvourney, Co Cork, is one he has happy memories of despite its dark subject matter. “I do have very strong memories of Song For a Raggy Boy and it’s among my favourites,” he says.

“It put me together with Aisling Walsh again, who was a great friend and still is. It’s an awful part of history. And I thought that the film portrayed it very powerfully and very accurately.

“I played a very disturbed man and all the kids were slightly scared of me, because they were at an age where they didn’t see a division between actors and and the roles that they’re playing. I remember the last weekend just before we wrapped, I took them all out. We went and hung out and saw a film together and did different things.

“It’s amazing how much in denial the higher echelons of the church were and politics and society too. You need to keep banging on the door for it to be really broken down and owned up to comprehensively and fully and certainly the film was one of the early knocks in the door, I think.”

]www.corkfilmfest.org[/url]

Parenting a young family during initial Covid restrictions made for a busy household, but when Glen turned to culture he found comfort in reading and his guitar.

“It’s been a tricky time for everyone. I’d love to say that massive new things opened up but to be honest, it’s really very pragmatic: how do you cope with young children when they’re in the same house all day?

“I’ve got young kids as well as older ones. The home education was a challenge that was very preoccupying. I play the guitar and that’s always a means of getting away from it all a little bit. William Boyd was a writer who opened up to me. I’d worked with William on a film that he adapted the screenplay for. And then I did a play of his called Longing.

“He was very present in the rehearsal for that and he’s a lovely man, but I’d never read any of his writing. I just started to read a William Boyd book and I just couldn’t stop reading. So during lockdown, I read about nine William Boyd books, starting with Any Human Heart.”

![[Book Review] The Blade Itself (The First Law Trilogy) by Joe Abercrombie](https://bendthekneegot.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/01/1516047103_maxresdefault-218x150.jpg)