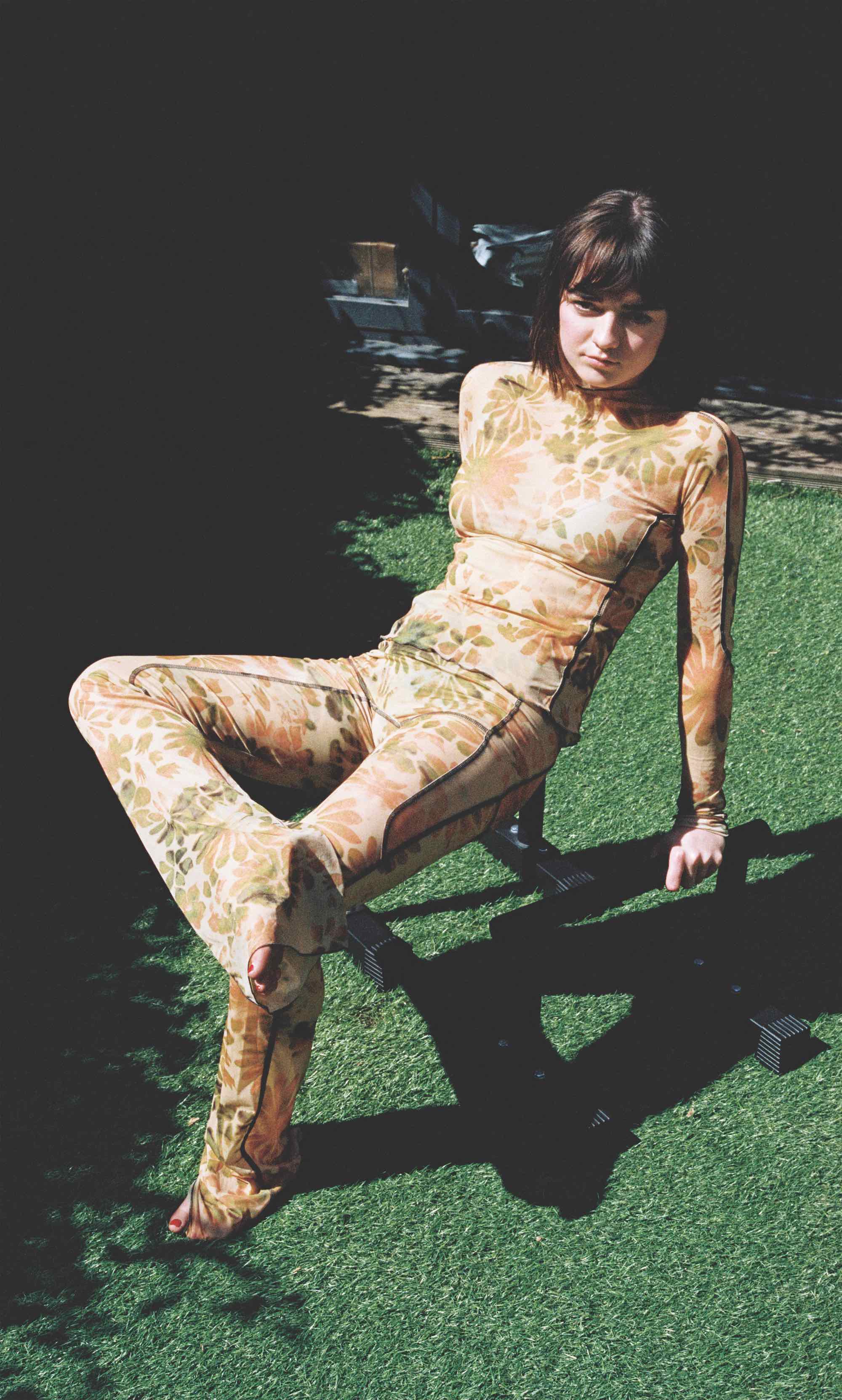

The Game Of Thrones star talks life after the cult TV show and what’s next.

All clothing CHARLOTTE KNOWLES

Taken from the Summer 2020 issue. Order your copy now.

Maisie Williams is quite enjoying being in lockdown when I call her at home on a drizzly Monday morning in London. “I actually don’t really leave my house much anyway, so it feels quite nice,” she laughs. Our call is exactly a year to the day since episode three of Game of Thrones’ final season — ‘The Long Night’ — aired; a year to the day since Arya Stark niftily dropped her dagger from one hand to the other before plunging it into the chest of the Night King, the show’s chillingly supernatural — and until then, insurmountable — antagonist. While fans everywhere still mourn the conclusion of the show that dominated cultural discourse throughout the 2010s however, for the actor who played its tenacious young lead, the end was more than welcome.

“It’s been nice taking a step away from it all, definitely,” Williams exhales. “I feel quite relieved still, to be honest with you. [Season eight] was a lot to shoot, and then when it came out the hype around it was so overwhelming. I don’t know that it could have got any bigger, so it was nice that it stopped.” Having joined the show at 12, Arya being Williams’ first acting role in any professional capacity, Game of Thrones has dominated the actor’s life for the best part of a decade, and it’s hardly surprising that she is relishing her time off, the relief palpable as she explains how “you’re so stuck in the schedule of shooting and promoting that your whole life just ends up revolving around the show, and you don’t really get any time for yourself, so it’s been really nice to leave all of that behind.”

For those outside of the fray, Game of Thrones and the cultural hysteria that surrounded it was unlike anything seen before on television. As fans and detractors alike will attest, the show’s final season essentially broke the internet every time an episode aired, incessantly dominating workplace conversations and news feeds everywhere, week in, week out. This was to be expected of course; much like any of its smash-hit predecessors — from Lord of the Rings to Harry Potter — the intricacy with which the fabric of the story was woven enabled viewers to truly immerse themselves in the narrative, the show’s problems becoming theirs, its victories celebrated as profoundly as if they were occurring in reality. Arya’s dagger-drop a year ago was one such moment, simultaneously uniting millions in communal, real-time exuberance in a manner that transcended fiction, not too dissimilar to when Usain Bolt broke the 100m world record in 2008, or the moon landing. Despite the dragons and magic, for that one second, Arya’s success felt real, and this was inevitably a huge constituent factor in Game of Thrones’ success over the years.

All clothing CHARLOTTE KNOWLES

However, with this veneer of actuality come problems. The show’s much-contested ending unearthed a darker side to said fanaticism, the strange notions of ownership and entitlement rearing their heads, and Williams gives an insight into the fans’ unique and often problematic relationship with the show. “It is weird because people think I am [Arya],” she explains, her voice frowning somewhat.

“They think I’m the character, and they want to ask me why the character did something like we’re the same person. That’s weird to get your head round, because I feel very different to the characters that I play; it’s strange to have to entertain that because it’s such a bizarre concept. It’s actually nothing to do with me […] It’s up to you to think about and decide for yourself, you know? There’s no right and wrong answer to understanding a TV show, it’s just your opinion.” While a jaded sense of entitlement saw some fans reject the endings bestowed on their favourite characters by the show, for Williams, Arya’s swansong still makes perfect sense one year later. “I feel very pleased with the way that it ended for Arya,” she says, almost defiantly. “I feel like the character was wrapped up really well, and she had a pretty positive ending which is all I could have really asked for.”

Though Williams’s character in upcoming project Two Weeks to Live is similarly gutsy, the comparisons between the Sky original and Game of Thrones are few and far between. Here, she plays Kim Stokes, a young misfit whose father passed away under suspicious circumstances, and who is brought up in rural, isolated conditions by her mother, Tina (Fleabag’s Sian Clifford), who has taught her an array of bizarre survival techniques along the way. When Kim finally pursues a normal teenage life things get messy, with gangsters and police alike on the hunt for the survivalist duo. The show rejects genre confinement, instead gleefully residing in that venndiagramatic sweet spot between action, comedy and drama, in a wonderfully The End of the F***ing World-esque way. “It’s definitely very funny,” Williams enthuses. “It has really lovely notes of drama and action but, at the heart of it, it’s a very funny show. I think for me it was very important after Game of Thrones to do something that was contemporary, but also that was tonally very different, that didn’t take itself too seriously. I think with Kim and Two Weeks to Live, I’ve really been able to do that.”

Dress MAISON KITSUNE

Through Kim’s eyes, Williams relished the chance to communicate the absurd-yet-accepted minutiae of daily life, and this was indeed a large factor in her decision to join the cast. “I read the project a couple years ago and […] I just thought the concept of a young girl who comes back into civilisation, and her take on the world, was so interesting […] She escapes to look for a new life, gets out into the real world and realises that everything is so backwards and strange,” Williams explains, clearly enjoying the way in which Kim’s outsider’s view of a world she hasn’t yet experienced allows the show to question society and the status quo. “I think seeing the world through Kim’s eyes that way is very interesting […] picking up on all the things that we think are normal, that don’t make any sense,” she says. At a time in which society as a whole is being forced to collectively examine itself and its behaviour, Two Weeks to Live seems pertinent, though Williams is also keen to emphasise the show’s remedial comedic qualities as well as its social perceptiveness. “I hope that people get enjoyment in a new way, and get to laugh at this show while also connecting on a really sincere level with this character who’s lost in the world,” she tells me. “I think that’s very beautiful.”

Since time immemorial, it has been a bleak reality of film, theatre and television that female characters are portrayed stereotypically and over-simplistically; if you apply the Bechdel test to Shakespeare’s plays, there is just one scene (in Henry V) where two women talk to each other about something besides a man, and this tradition has unfortunately persisted into today’s media. Even Game of Thrones, a show often bestowed with the tokenistic defence of having ‘strong female characters!’ is an example of this, with only 18 episodes out of 67 passing, and this is before you even bring its gratuitous use of female nudity and callous treatment of sexual assault to the conversation. The Bechdel test is, of course, not the be all and end all of female representation in media; just because something passes doesn’t automatically make it truly inclusive and diverse, and indeed the opposite is too often true. However, for a show with such a wide audience that utilises its female characters as heavily in marketing and promotion as Game of Thrones does, that number is appallingly low, and Williams believes there is still some way to go before the industry can truly boast equal representation.

All clothing CHARLOTTE KNOWLES

“We can do more,” she asserts. “I still feel like there are tropes of who incredible women are, and that’s mainly due to the fact that we still have so many male writers and directors, so it’s down to female actresses to warp a script and character into something more interesting. Until we have more female writers who are celebrated, and more female directors who are given these great women to direct, you’re still going to have a mismatch.”

“You’re never going to understand what it’s like to be a woman and I’m never going to understand what it’s like to be a man, and that’s absolutely okay,” she continues. “But as a director, [you] should stop pretending that [you] do know how to be a woman. We have so many roles written for women now, and you have all these great women being celebrated at the Academy Awards and they are phenomenal. But until the female directors and female writers are recognised, you’re constantly going to have actresses playing roles that aren’t quite right.”

Characteristically, Williams is being the change she wants to see in the industry. She is currently in the middle of creating an as-yet-unnamed limited series shot entirely in quarantine, and Williams speaks at length about her fascination with the way the Covid-19 pandemic has encouraged innovative ways of communication, and the effect this has had on productivity. “There are so many distractions, so much media that you can consume through your laptop, that it’s hard to switch off and do work,” she explains. “So we basically just thought of the idea of shooting it through your laptop, which could be kind of cool.” Currently working on the project via — ironically — Zoom, Williams is enjoying the chance to build something of her own during the lockdown, and she extolls the overwhelmingly female-driven nature of the project thus far. With the director, writer, cast, lead producers, DP, 1st AD, costume designer, hair and makeup artists and even grip (“you never get female grips”) all being women, I ask if there is a tangibly different atmosphere on set, and Williams’s answer is almost instantaneous. “Yeah, definitely — it just felt right,” she avows. “When you’re working with men there’s a hierarchy; there’s always someone who is the leader. When you have a male director, a male 1st and a male DP — and every single one of them wants to be the star of the show — then as an actor you’re sitting there and watch- ing this mess unfold in front of you, where boys are fighting over the most stupid things.

All clothing CHARLOTTE KNOWLES

Though she is resigned to this not always being the case going forward (“I have worked with men my whole career and I will for the rest of my career,” she laughs almost begrudgingly), the dynamic is certainly something to aspire to, and Williams is hopeful that the wider industry will eventually grow to allow women more of a say behind the lens, as well as in front of it. “There’s so much that can come from women working together,” she says passionately. “We are so powerful when we work together and I think it’s exciting [to think about] the stories that we could tell if only we were given the opportunity.”

It might seem surprising for an actor coming fresh off the back of such a major series as Game of Thrones to work on independent projects, and rest-assured, Williams will be back on the big screen soon, set to star in the latest X-Men instalment: The New Mutants, alongside Charlie Heaton and Anya Taylor-Joy. However, this dedication to creativity, and to the art itself, is part of the actor’s whole ethos, a mindset she succinctly summarised during her TEDx talk in Manchester last year, when she said: “don’t strive to be famous, strive to be talented.” As an alum of perhaps the most hype-driven show in history, it’s refreshing to hear Williams laud the “true artists” of today, citing British designer Charlotte Knowles as an example. “Sometimes the over-hyped-ness can really ruin an up-and-coming designer and stunt their creativity. I think Charlotte Knowles is someone who is viewing it really organically; she’s still got something very unique, and there’s no one who’s doing anything quite like her right now, which makes me very excited.”

This notion of fame for fame’s sake is rife in film too, and Williams is all too aware of the power of social media — and the intrinsic rewarding of popularity that comes with it — is beginning to have on the industry. “I think there’s a new way of getting to the top,” she deliberates after a pause, “and it has more to do with social media and fame than it has to do with substance and quality.” Through giving her time to projects like the limited series, Williams hopes to counter this popularity contest, dragging the focus back onto the art itself and allowing her to do projects that mirror her interests, rather than popular demand. “Despite being part of one of the biggest shows on earth, I don’t know that — if I wasn’t on the show — I would necessarily watch it,” she muses. “I know that loads of people say that, and then all of a sudden they [fall] in love with it, and that could be the case for sure. But in terms of that sort of genre it’s really not my thing at all, so what excites me about the future […] is something that resonates more with my personality, and my taste.”

Such is the integrity and fluency of the actor’s words that I am somewhat brought back to reality by her publicist’s gentle reminder that we only have time for one more question, and I ask Williams whether she ever thinks about posterity, and the way in which the lasting cultural impact her work has had (and will inevitably continue to have) will shape public perception of her in years to come. “It’s kind of strange”, she says, “because I feel like I will be defined as Arya Stark, and the show will define the work I have done. But, I think even already Gen Z don’t care about Game of Thrones, and as the world goes on, we’ll only get more and more generations of people who didn’t watch the show. Ultimately, as you become an older actor, the people who create your career are going to be younger than you — that’s just the way it goes. So I think, although for a certain demographic I will be known as Arya Stark forever, I am Gen Z, and I don’t feel like that has defined my life.”

This is, understandably, something Williams has clearly thought long and hard about, and I am taken aback by the honesty and introspection with which she speaks about her own position, in the industry, in culture, and in the world. After a brief pause, she continues. “I want to be remembered as someone who did everything she wanted to do, and was unapologetic about it… So, if anyone ever sort of looks back on me, if I ever do anything else, I just hope people respect it as something I felt passionate about. I’m so lucky to do what I love, and if you’re not passionate about the projects that you’re part of, and not happy even though you’re in one of greatest industries ever, then what’s the point?”

![[Book Review] The Blade Itself (The First Law Trilogy) by Joe Abercrombie](https://bendthekneegot.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/01/1516047103_maxresdefault-218x150.jpg)