The following paragraphs are either directly excerpted or paraphrased from Patrick Brown’s 2018 book, Take Down, an autobiographical account of his rise and fall within the Ontario PC Party:

“By the time I announced my intention to run for Ontario Party leader in October [2014], I had lined up all sides of each of these communities—the four sides of the Sikh community and the three sides of the Tamil community.”

“The Tamil community organizers told me when I announced my candidacy that they would be able to sweep the GTA for me.”

“During the campaign, we signed up around 10,000 Tamil members.”

“In key ridings such as in Scarborough, where there were about 20,000 Tamil families per riding, my campaign team knew it would be a cakewalk for us. But I said to the team that the goal was to find Tamil families in other ridings.”

“In the weaker ridings, if we could get 500 Tamil members signed up to vote, we knew we’d have 80 per cent of that riding.”

“This guy’s our hero,” Tamil organizers would tell families, to persuade them to take out PC riding memberships and turn out to vote for Brown when the leadership race was held.

Image Facebook

“In northern Ontario, we looked to find Indians and Tamils. It turned out that in Thunder Bay, there was a 500-member Indian community.”

“Pollster [Brett] McFarquhar kept telling me that there was no way I could beat [Christine] Elliott because I was only at two per cent in the polls, and the margin of error was only three per cent. But early on in the leadership campaign, I said to McFarquhar, ‘Actually, you know what? You’re wrong. It’s already over.’ I knew because I had gone out and visited all the leaders of the Tamil and Indian communities, and each community had a presence in the majority of ridings in Ontario. I had the support of all the top organizers in both communities.”

Brown wrote what he believed Tamils thought of him ahead of the 2015 Ontario PC leadership race, that “This guy’s our hero”.

The blindly ambitious politician, like others of his ilk in all walks of life, is better at borrowing ideas to elevate himself while too consumed to develop any personal set of values that attracts people to true leaders. He had stolen the ethnic playbook from Jason Kenney (who likely took it from someone else). The former Canadian immigration minister seized upon Sikh Canadians a decade-and-a-half ago, salivating over the tens of thousands of community members who could fill huge venues, stuff party coffers and swing entire ridings.

It was part of the grassroots strategy the current Alberta premier pieced together with politically ambitious so-called community leaders from a number of vote-rich ethnic blocs across Canada during his one-year stint as Stephen Harper’s “Secretary of State for Multiculturalism and Canadian Identity” before serving for five years as federal immigration minister from 2008 to 2013.

The prior role involved Kenney attending ethnic celebrations and community events to get a foothold in some of the largest constituencies of Liberal voters.

Kenney quickly learned and, unlike the Liberals, eventually voiced concern that playing identity politics in ethnic communities vulnerable to exploitation, could lead to the type of deep internal divisions and destabalizing external problems on the international stage that Canada should avoid, for the best interest of the entire country.

His ethnic strategy, which amounted to little more than patronizing (both definitions) events and voters, eating traditional foods, uttering practiced greetings and salutations in mother tongues, appealed to many self-styled community potentates who made a name for themselves in business, organizing around old-world issues or temple politics (the latter two are often intertwined).

They were made for each other.

The photo-ops were plastered by both sides: the Conservatives to show voters their interest in them after the Liberals had taken them for granted; and by local opportunists to show-off their connections and alleged political clout with the party of the future.

The Liberals didn’t know what hit them and Kenney helped the Conservatives score key victories for the Party’s nine-year hold on government, especially in suburban ridings outside Toronto and Vancouver.

But the marriage was short-lived.

Grassroots groups and voters realized the Party offered few policies to actually make their lives better, while Conservative immigration and labour platforms under Harper worked against their interests.

Kenney, meanwhile, grew tired of the demands and internal strife within many of Canada’s most complex ethno-religious diaspora groups. He had never wanted the ministerial role, having actively avoided immigration portfolios earlier in his career, before he and Harper hatched their plan years earlier to repopulate the stagnating Conservative Party by introducing newcomers who didn’t look like them into the tent.

That was before both sides realized it was a bad fit from the beginning.

“Certain groups have sometimes tried to wield my prominence to advance their cause,” Kenney told Maclean’s Magazine’s Quebec-based sister publication, L’actualité, in 2012. He had just hastily withdrawn from a religious gathering that quickly turned divisively political, the reporter in tow. “I have to be vigilant at all times. They shouldn’t be encouraged to reproduce, in Canada, the tensions of their homelands.”

The Liberals won 184 seats in the 2015 federal election, 148 more than the previous one. Much of the ethno-religious vote had peeled away from the Conservatives, a mismatch from the beginning engineered by a politician who never had any real plan to reimagine his party as a truly progressive force.

Neither does Patrick Brown.

When he picked up Kenney’s playbook and dusted it off to win the 2015 PC leadership, the Tamil community was a main target.

Unlike the national party’s widely public efforts around a federal election, Brown could work quietly within specific ethno-religious communities to sell Party memberships. Genuine Conservative values and the direction Party loyalists wanted to move in, didn’t matter. The faithful could fight among themselves. Candidates like Christine Elliott were so far ahead of Brown in the polls they didn’t even pay attention to his campaign, which exploited a fundamental flaw in both the PC and CPC leadership election system.

Brown could either go into enough strong PC ridings that had low membership or Liberal and NDP-dominated ridings where PCs barely even made an effort to sign members. Because the leadership race converts votes into points with a cap of 100, Brown could game the system (when more than 100 registered members in a riding cast a vote the numbers are converted to percentages representing how many of the 100 points go to each candidate).

If a riding only had 30 PC members (worth only 30 of the potential 100 points), Brown could use 70 Tamil-Canadian names to win 70 of the 100 points. If a riding had 200 members already committed to other candidates, Brown could register 200 more and win 50 of the 100 points. He would avoid ridings where his competitors had too many members. Because each riding represented 100 points, even if someone like Elliott had thousands of members supporting her in traditional PC strongholds, far outperforming Brown among the overall membership, which the polls clearly showed, he could still win the overall race by getting more points, focusing on ridings where far fewer memberships would be needed to maximize the number of points up for grabs.

Tamils and other South-Asian Canadians, mostly in suburban Toronto, but also in many more remote ridings where just a few dozen memberships could secure Brown valuable points, won him the PC leadership. Elliott and others might have had ten times the support, representing the desired direction of true conservatives, but Brown had manipulated the math.

Along with the “500-member Indian community” he used to skew the point tally in Thunder Bay, “In Timmins, the guy who owned the local restaurant was a Tamil community member,” he wrote in his book (apparently Timmins only had one restaurant, or at least only one that mattered to Brown).

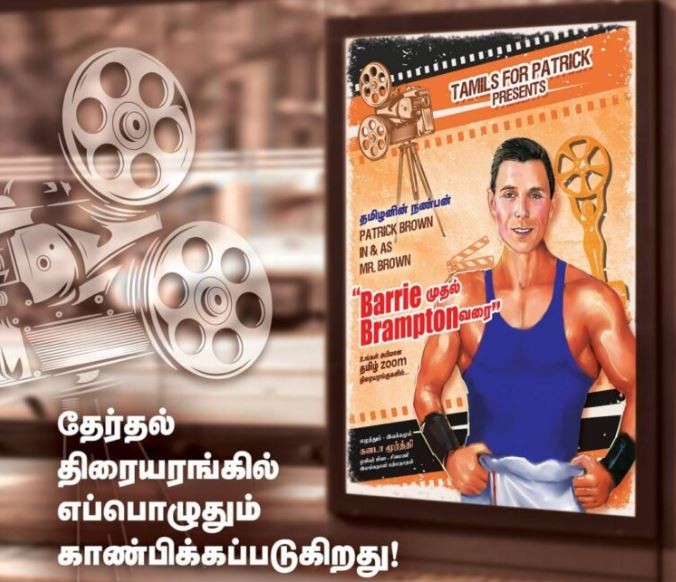

In a widely circulated article titled B2B—MR. BROWN: From Barrie to Brampton, published in a Tamil-language platform and translated into English, one of the community organizers who worked on Brown’s Tamil membership scheme, wrote that community members who helped pull together membership votes were promised that, “When Patrick Brown becomes the Premier of Ontario, Tamil people will be given higher positions in many government boards such as regulatory boards of LCBO.” Later, the article states, “…it became apparent that these kinds of emotional campaigns and attractive promises were the main reasons behind Patrick Brown’s popularity among the Tamil community.”

When Brown ran for Brampton mayor in 2018, “similar techniques were used once again on the Tamil community.” The article says the same promises of jobs for loyal followers were thrown out to the Tamil community. “Once Patrick is our Mayor, we will give municipality jobs to Tamils living in Brampton.”

After he was elected by voters who now feel betrayed, many in Brampton’s Tamil and Sikh communities asked what happened to the high-paying jobs Brown promised; those went to his white male Conservative-insider friends from places like Barrie and Niagara.

The article goes on to detail how the broader promises Brown made to the Tamil community were actually plans that had been established long before he became mayor, by local groups and elected officials Brown took the credit from, such as Councillor Martin Medeiros who had done much of the council work to help get a Tamil monument built in the city.

The article asks, “What has Patrick Brown delivered fruitfully to the Tamil community…?”

It also cautions against politicizing issues such as the civil war in Sri Lanka, which pitted Tamils, the largest ethnic minority group, against the Sinhalese, who make up almost three quarters of the population and control the government.

Brown, of course, ignored these warnings, using his meaningless words and gestures of support for the Tamil position around the war, which ended 13 years ago, to whip up a base to propel his political ambitions.

Now, as he seeks the CPC leadership, his focus has shifted to Muslim communities across the country.

Once again, Brown is dangerously dividing Canadians in a shameless effort to use demographics in his favour.

Muslim Canadians could do what Tamils and other South Asian-Canadian voters did for him in 2015.

His exploitation of these communities has only recently been confronted.

Within the past few weeks he sent out a string of tweets and other social media messages in support of Palestinians seeking international assistance, and in an interview with a Montreal-based publication with a large Arabic-speaking readership, he said of the ongoing Palestinian-Israeli conflict, “Canada is simply replicating the position of Washington DC and Donald Trump.”

He also broke ranks with the Conservative Party position, pledging he would move the Canadian embassy out of Jerusalem, something Palestinian’s want, but Israel does not (after widespread backlash from Jewish Canadians, Brown flip-flopped).

His sudden support for Palestinian rights flies in the face of his position in 2016, when as PC leader he flatly rejected the Palestinian BDS (boycott, divestment and sanctions) movement to impose economic measures against Israel, instead voting in Queen’s Park for a motion to “…recognize the longstanding, vibrant and mutually beneficial political, economic and cultural ties between Ontario and Israel… and reject the differential treatment of Israel, including the Boycott, Divestment and Sanctions movement.”

Brown’s words and actions (or lack of action) seldom match.

The Canadian Jewish News recently published a first-person piece by writer Josh Lieblein, who made the point that Brown will say whatever a room full of potential supporters wants to hear: “… I once stood not 10 feet from Patrick Brown and heard him speak to an audience of Canadian Jewish Political Affairs Committee donors at a fundraiser. He spoke for perhaps five minutes, said the pro-Israel things he knew everyone wanted to hear, and then fell silent,” knowing he already said everything he could to win the support of those gathered around him.

Whether it’s playing Palestinian-Canadians and Jewish-Canadians off each other or trying to manipulate vulnerable citizens to win a few more membership points by telling Ukrainian-Canadians he would effectively support a third World War to help their cause (he then used the widespread support for Ukrainian refugees to stir resentment among Palestinians) Brown only cares about one thing—power.

It’s a dangerously divisive game to him, one that shows, as Lieblein put it, “…how Brown treats people as a means to an end—and how others treat him in a similar fashion. There are countless other such relationships, and this is how we know groups…and individuals…are praising him not because they care about any of the enormous red flags hanging about, or because they are in any way conservative, but because having a person with name recognition that appears to pander to them validates their existence in a way that nothing else could. And now, they will offer themselves up to him, body and soul.”

In a recent leadership debate that Brown skipped, moderator Jamil Jivani said, “Some Canadians are concerned that Mayor Brown is sowing division in our country. He has been criticized for manipulating diaspora politics to bolster his campaign,” then invited candidates to respond.

“The bottom line is that Patrick Brown says one thing in one room and exactly the opposite in another room,” Pierre Poilievre replied.

Another warning sign to groups Brown is hoping to exploit while sowing further division, is his supposed desire to see Quebec’s Bill 21 defeated.

The problem? His claim goes against everything his political mentor, and “big brother” Narendra Modi stands for. This is what Brown said of his political idol in his book: “…one of my inspirations in politics was Modi…”.

Patrick Brown with his “political inspiration” and “big brother”, India’s authoritarian Prime Minister Narendra Modi.

(Image Facebook)

Brown said he has used Modi’s campaign tactics and even borrowed a slogan the Indian prime minister had used to help him gain power.

Two of the most widely respected publications in the world have recently described Modi and his barbaric treatment of India’s 200 million Muslims.

The Indian prime minister was recruited into the R.S.S., a militant Hindu-nationalist organization fashioned alongside the fascist movements that arose across Europe in the 1920s, when he was just eight. Modi is leader of the BJP, the political offshoot of the R.S.S. whose organizing principle is that Hindus must erase all existence of Muslim identity in India. Modi’s hatred for Muslims defines his leadership and he has snuffed out the free press and subverted the courts to suffocate democratic safeguards.

When he was head of the state of Gujarat, Modi stood by while thousands of Muslims were murdered by Hindu mobs during three months of communal rioting, and despite mountains of evidence that he orchestrated the killings he escaped without being charged.

The New Yorker magazine recently asked Indian human rights labour lawyer, Indira Jaising, how “Modi’s authoritarian run might be overcome”. She replied, “Ideally, it should end in a political defeat in the manner that Trump’s run” did. “But I don’t see that happening. . . . He has mesmerized a whole country into collective hatred and othering of the Muslim community.”

A recent piece in The Atlantic included this description of Patrick Brown’s “political inspiration”, describing Modi’s brutal law that strips Muslims of statehood: “India’s Muslim population of almost 200 million, which had been provoked by Modi’s government for six years, finally erupted in protest. They were joined by many non-Muslims, who were appalled by so brazen an attack on the Indian ethos,” calling Modi’s fascist law “an arrangement in which being Indian meant accepting Hindu dominance and actively eschewing Indian Muslims.”

Modi has also undermined Sikh autonomy in India and around the world, but Brown, despite being mayor of a city with one of the largest Sikh communities outside India, has refused to call out his political idol, even when claiming to support Sikh-Canadians who, with no help from Brown, continue their fight for religious protections, here, and around the world.

Brown has travelled to India some two-dozen times, often invited by Modi. He bragged about the prime minister’s appearance on stage with him at a rally Brown organized during the PC leadership race. But you won’t see Brown on his current campaign drive to sign up Muslims mentioning to them his “big brother” Modi’s barbaric actions, while claiming to support the Palestinian cause, or fight against Bill 21.

The politics of division is boiling over across much of Canada and the world. Electing a man like Patrick Brown is like pouring kerosene to stop a fire.

COVID-19 is impacting all Canadians. At a time when vital public information is needed by everyone, The Pointer has taken down our paywall on all stories relating to the pandemic and those of public interest to ensure every resident of Brampton and Mississauga has access to the facts. For those who are able, we encourage you to consider a subscription. This will help us report on important public interest issues the community needs to know about now more than ever. You can register for a 30-day free trial HERE. Thereafter, The Pointer will charge $10 a month and you can cancel any time right on the website. Thank you

![[Book Review] The Blade Itself (The First Law Trilogy) by Joe Abercrombie](https://bendthekneegot.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/01/1516047103_maxresdefault-218x150.jpg)