“Theon wondered what it would be like, to have a home.”–“The Prince of Winterfell,” A Dance with Dragons by George R.R.Martin

In Game of Thrones’ penultimate and seventh season, with the end in sight, audiences began to see a rare occurrence in Westeros’ fractured world as widespread reconciliations and reunions reigned supreme. With only six episodes left before the finale of the show, it is only appropriate that Thrones, which premiered in 2011 and made a name for itself with its brutal disregard for the feelings of its characters, begins to set the scene for its long-promised “bitter-sweet ending.” And there are few things sweeter in a world of chaos and instability than having a place to call home.

In keeping with the genre trope of plots oriented around quests, catharsis epitomized by the act of coming home after a long and difficult adventure has enjoyed a strong and well-established foothold in the fantasy tradition—thanks in large part to Tolkien and his homebody Hobbits. Perhaps this is because such a trope provides an idea of just how far the character has come since the beginning of the story. A home or hometown which represented the identity of the character at the beginning of the their adventure, may clash with the newly developed personality of the character thanks to the experiences they have undergone, as the quest, and the story reach their end. This offers a final cathartic conflict as we see the character use their new skills and self assurance to repossess their home and redefine what it means to them after a period of transience and change. The audience and the character find a final challenge and sense of accomplishment as the character reclaims their heritage and reconciles their present with their past, something which often takes place in the home, an unchanged, and oft longed for representation of security and self. This trope is complicated, however, when the character, unlike the well-established Bilbo Baggins of Bag End, or the Starks of Winterfell, must find a form of resolution in the face of displacement and alienation.

Game of Thrones carried on this narrative tradition in Season Seven, perhaps most memorably when the first episode ended in a sedately triumphant moment as Daenerys Targaryen, long exiled from the very continent she is from, returns to the episode’s titular Dragonstone. The castle is desolate and decaying, but for Daenerys, who compromises her regal airs to stoop and touch the land of her people, she is home in a very visceral way. Daenerys has returned as a conquering queen, in a long line of Targaryen rulers, to the place she was born, and while the war for Westeros is hardly won, a more personal battle of belonging that she has been waging for years is finally, quietly ended.

The concept that simply returning to a physical home, even if one has no memories of living there, can cement one’s personal sense of heritage, and strengthen one’s resolve is a common one. It’s an especially potent idea when dealing with members of royal families, who often found a great deal of their self-worth on the accomplishments of their forefathers (Daenerys when alone and powerless, and sold into a marriage with a warlord, takes comfort in the fact that she is a “dragon.” If even far from her family home, she is reassured by her ancestors’ tradition of strength and scale-like invincibility, it is clear why she feels revitalized to return to her family seat—Dragonstone). Dynasties are forged with bricks as much as blood—there is a sense of stability and security that comes from living in a stronghold that your great-grandfather has presided over.

When he returns to his birthplace and birthright, Pyke, in Season Two, after nearly ten years of absence, Prince Theon Greyjoy expects to experience a moment upon arrival similar to the revelatory and empowering one Daenerys would later experience. He wants to step onto the stony shore of the Iron Islands and finally know in his heart that he is in a place where he belongs. Like Daenerys, Theon has spent the majority of his formative years far from home. Raised as a ward of the Starks in Winterfell, Theon was not only in constant danger of execution if his father misbehaved, but also painfully out of place—a pain that was only intensified by the Starks’ polite denial of it, even as they urged each other never to trust him. “It’s not your duty because it’s not your House,” Robb Stark, who Theon gets along better with than anyone, lectures him when Theon passionately urges him to go to war for Ned Stark. Robb is happy to have Theon’s help, and friendship, but not his demonstrations of affection for Eddard– after all, Robb reminds him, Ned is not his father, and he has no right to rage over Ned’s suffering.

A member of a royal House but raised in the home of another, Theon is disappointed when he returns to a cold welcome by his own father, Balon. Theon had hoped to help forge an allegiance between Robb and Balon, to defeat the Lannisters who have killed Ned and captured Robb’s sisters, but his father latches on to the idea that Theon is out of touch with his own family (Theon troublingly suggests that he considers Robb a brother even as he fails to recognize his own sister), and thus, hopelessly out of place. Balon rebuffs Theon’s call for unity with the North and mocks his lack of understanding of the Iroborn culture, informing him that, ultimately, “Your time with the wolves has made you weak.”

Despite the assumption that Theon must be a Stark loyalist, he was truly never accepted by the wholesome, tightknit Starks, who, while valuing his loyalty, have for the most part held him at arm’s length as a wild and untrustworthy savage (a label which was once founded on a stereotype and affixed to an innocent little boy, but was slowly realized as the little boy grew up). Thus, Theon has grown to define himself in colorful opposition to the Starks’ virtuous way of life, a flailing sea monster thrown out of the water and into a nest of sharp toothed, fluffy pups.

Upon going to Pyke, Theon is disconcerted to discover that his idea of what being a Greyjoy means is completely wrong, and he is perhaps more agitated to learn that the respect and love he expected to find in his “home,” is markedly absent. Balon strikes his son when he reminds him that he gave him away as a child, as an appeasement for Balon’s failed rebellion.“You gave me away like I was some dog you didn’t want anymore,” Theon cries in anguish, “and now you curse me because I’ve come home.” The difficulty is that Theon thinks Pyke is his home. Balon already discarded him as a son nine years ago, and there is no place for Theon at Pyke.

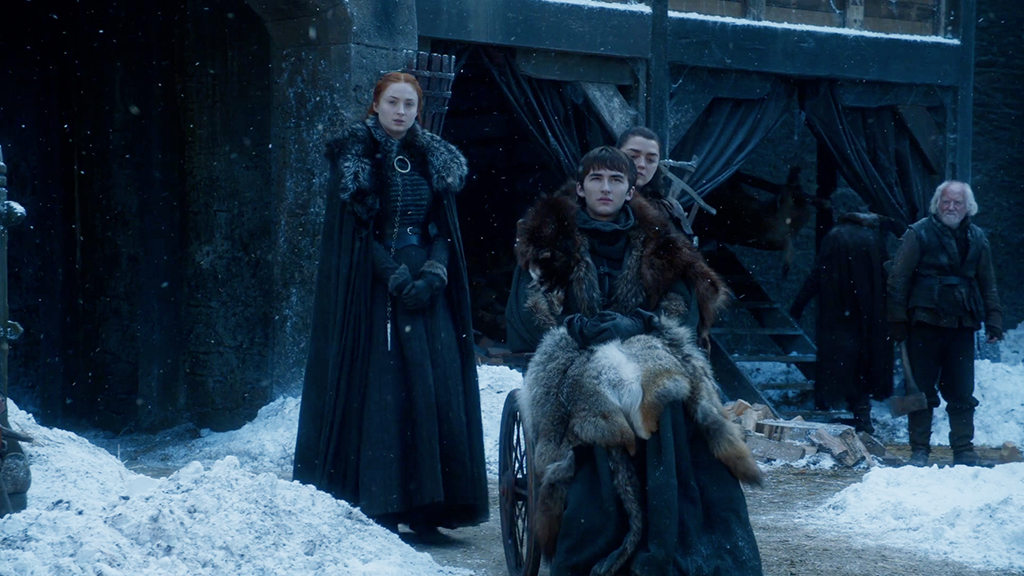

Just as Theon is forced away from his family unit and place of birth as a young child, the Starks also find themselves scattered as the show goes on. Happily, Season Seven saw the remaining Stark children finally reunite in their family home of Winterfell. Despite the fact that the castle had been damaged and desecrated, and is far from the warm fortress of unquestionable safety they once considered it, Winterfell is still a potent place to rally to. In a similar manner to the way that Daenerys returns to the cold, crumbling castle of her ancestors, not because it is physically welcoming or structurally sound, but because it is emblematic of the sense of familial strength and purpose she has cultivated and seen blossom, so too the Starks come home, one by one, not because the castle is truly impenetrable, but because they seek the unity and comfort of their family unit that their castle represents.

Recently many were saddened when news leaked that Winterfell will burn again in the final season of the show, not because many will truly mourn the castle itself (though the architecture is lovely!), but because it has become personified to an extent as a representation of the essence of the Starks, not only as a House, but as a family. While the Stark children’s direwolves represent their more individualistic identities, Winterfell has always stood for the Stark family as a united whole (something Ned Stark believes is truly important: “The lone wolf dies, but the pack survives.”) If the Stark children are wolves, Winterfell is their den—a place of nurturing protection at best, and a solid wall to put their backs to and bear their fangs at the worst. When Winterfell first went up in smoke at the end of Season Two, audiences were distressed because it felt as if the family, without a place to return to, was irrevocably disarrayed. For many families, the home is the most obvious symbol of unity, but at the same time, it is the unity that forms the home.

Later in Season Two, rebuffed by his father, Theon returns to Winterfell, this time not as a guest or prisoner, depending on how you spin it, but as a conqueror. Using his intimate knowledge of the castle, he captures it easily, but struggles with holding it as much as he struggles to define himself as a Greyjoy rather than a Stark. Theon sees a reconciliation within himself between Stark and Greyjoy sentiments as impossible, and he finds himself doubling down on the sense of brutality he imagines a proper Greyjoy must evince (he doesn’t do a very good job—“You’re not the man you’re pretending to be,” Maester Luwin counsels him, and Theon knows it, but the difficulty is he knows better what he’s pretending to be than who he actually is).

When Winterfell goes up in smoke, Theon disappears. After she learns of the abuse of her brother, Theon’s elder sister, Yara, declares she is going to sail down to the Dreadfort and free him the clutches of the Boltons, who have sacked Winterfell, killed Robb Stark and his followers, and taken hold of the North with the blessing of the Lannisters. When night falls, the Ironborn gamely clamber up the walls of the Bolton stronghold, which boasts macabre décor and denotes the House priorities of terror and treachery in its very name. The castle is currently inhabited by Roose Bolton’s bastard son, Ramsay Snow, who is eager that everyone know the fort is his home, despite the vexatious matter of his illegitimacy, and the fact that, like Theon, he did not grow up within the walls of his father’s abode. Also like Theon, but additionally spurred on by a healthy dose of depravity and turpitude which Theon could never hope to attain, Ramsay overcompensates for the lack of acknowledgement on the part of his father by attempting to be the perfect Bolton in all but name. Not surprisingly, perhaps, for someone who calls the Dreadfort his home, this involves a great deal of dreadful behavior, the fallout of which Yara isn’t exactly prepared for when it comes to Theon.

Yara finds Theon deep in the Dreadfort, surrounded by yapping mongrels. “We’re going home,” Yara informs Theon with gusto. But in the end, Theon does not go home. Yara eventually sails dejectedly back to where she came from, blood spattered and announcing to everyone she meets that Theon is dead—she can’t imagine an existence where the basic rallying cry of home is not compelling. In truth, the disaster of that night is just as much the fault of Balon’s abandonment as it is Ramsay’s persecution. Theon has never truly been secure in his knowledge of where exactly home is. Yara’s shorthand in a stressful situation, her attempt to promise him safety and family, doesn’t do a very good job of getting his attention because Theon has never had a solid, subconscious understanding of what hometruly means to him, other than as a vague unsubstantial desire which lies unfulfilled.

In the next episode, at Moat Cailin, exhausted and unwillingly complicit in the betrayal of his own people (incidentally all based on the foundation of a duplicitous promise that they could go home) Theon implores Ramsay if they can go home now. He means the Dreadfort, but the Boltons head for Winterfell, and drag Theon along. It’s a painful reminder that Theon can’t find basic stability or belonging anywhere, in any form. It is also a demonstration of Theon’s lack of freedom in his life: Winterfell and the Dreadfort have become conflated, both prisons that are simultaneously the only real homes Theon has ever had. Having legitimized Ramsay, Roose decides that he and his son will have a more authoritative hold over the North in the ancestral home of the Starks.

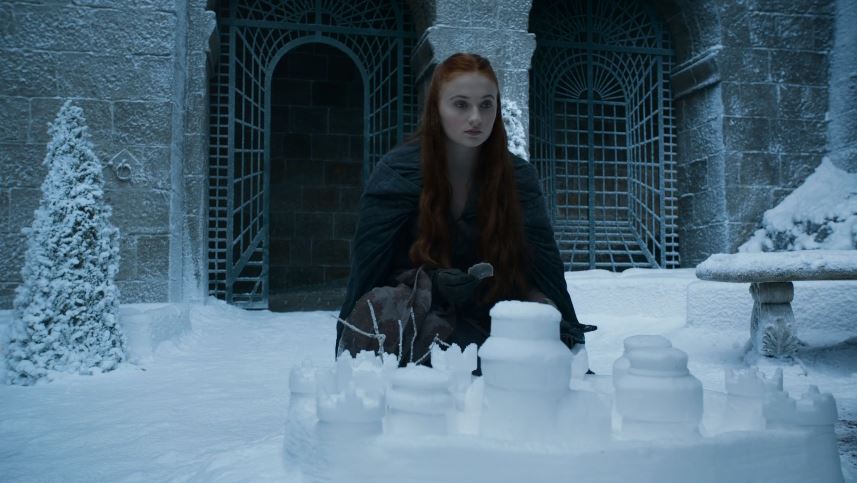

Trapped and tormented in Winterfell, Sansa and Theon clash because Sansa expects Winterfell to bring out the same sense of familial unity in Theon that it evokes in her. Theon, however, fails to find solace simply in the structural substance of Winterfell, perhaps because it was never truly his home to begin with, and a prison all along. He is unable to access the more ethereal providents of hereditary cultural narratives of strength and self-assurance that Sansa feels herself surrounded by and is forced to resort to finding motivation to escape from somewhere within himself and his own uncertain ideas of what it means to be the kind of person he wants to be, and that Sansa needs him to be, which is a very vague thing to sort out, even at the best of times. Despite her brave words, Sansa still finds herself confined by the place she once considered a safe and joyful home. It isn’t until she achieves a level of understanding and unity with Theon that they can avail themselves of Winterfell, now a twisted trap in the hands of the Boltons. The familial love and unity found between Sansa and Theon ultimately transcend the need for a physical representation in the form of Winterfell as a home, and they fling themselves off its walls.

After Theon and Sansa escape, Sansa seeks protection from her half-brother Jon Snow, who is currently Lord Commander of the Wall. Jon, who much like Theon never felt truly welcome at Winterfell or among the Starks, has gone on to establish his own family and sense of home at the Wall (“Here we are all one House,” his Lord Commander announces before Jon says his vows). Despite this, the foundations of Jon’s brotherhood have been shaken after an ill-advised assassination attempt. Theon suspects Jon will kill him, so he tells Sansa he can’t go with her. Sansa, looking truly confused, asks him where he’ll go. It’s an interesting question, because in practice it seems like more of a mystery where Sansa, her home invaded and her family dispersed and deceased, will find refuge, than Theon, but clearly Theon isn’t the only one with a shaky sense of where exactly he belongs in the world. The scene ends when Theon says simply that he will go home. At the time, this was the last of Theon audiences saw until the next episode, and there was some (needless, in my opinion, given the immediate cut to a scene on Pyke) speculation regarding just what he meant. A few suspicious viewers posited he would go right back to the Boltons. Other even more pessimistic viewers thought he would kill himself. In the end, however, Theon returns to Pyke a second time. And a second time, he is met with a cold welcome. Yara is angry at Theon’s unenthusiastic response to her grand rescue attempt, and unenthusiastic about his arrival right as she’s about to claim her father’s throne at the Kingsmoot. Theon assures her that he has no immediate interest in supremacy, favoring security, but he finds neither. His uncle, Euron, has arrived after a great deal of time spent abroad, which doesn’t stop him from claiming kingship of the Iron Islands, forcing Theon and Yara to flee.

Now both siblings are cast adrift, but Yara fails to comprehend Theon’s agitation at their vulnerable transience. Like Euron is firmly confident in his Ironborn authenticity, despite years of errant gallivanting, Yara is secure in her place in the world and no longer needs a physical place to call home to ground her sense of herself. Theon, who has always molded himself in opposition or accord with his general surroundings is uncomfortably left to his own devices. Yara tries to encourage and empower him by reminding him that despite having had some, “bad years,” he is, at the end of the day, Ironborn. She hopes this assurance will ground him in a greater cultural heritage, which is founded on blood rather than land, and emphasizes a fierce and fearless way of life that she thinks he could use a bit of. But Theon is acutely aware that he is only slightly less estranged and illiterate in his larger culture than when he blindly based his ancestors’ prowess on his own adolescent accomplishments. Moreover, his last attempt at embracing the Ironborn way of life ended badly– joyful acts of depravity do not sit well with Theon at heart. They do, however, for his cackling, pudgy uncle who demands the siblings’ attention with a stunning display of pyrotechnics that sadly fails to drown out his grandiose, B-movie commentary as he makes short work of the Sand Snakes and tussles with his niece before finally challenging Theon to one on one combat as the ship burns down around them. When Euron finally corners the siblings and devastates their fleet, the “bad years,” dominate Yara’s vague promises of Theon’s Ironborn sensibilities, and Theon finds himself alone again, in the sea.

Despite his conviction that he lacks a larger cultural fluency, Theon truly does embody the greatest and most important Ironborn sensibilities, which go much further than raping and raiding, in a way that supersedes his upbringing or experiences. The Ironborn, in theory, are a fearless bunch, because they have faced what terrifies them most– death. The Ironborn are not afraid to die, cultivating resilience through the promise of resurrection and courageousness that comes from overcoming calamity. Theon, more than anyone, has died and he has been reborn. As much as he believes he is dominated by fear, he repeatedly demonstrates the freedom of someone who is not afraid to die– he truly is ready fight to the death in a last stand for Winterfell, he jumps from towering walls, he confronts his foes, he kills a man with his bare fists, even as the man tells him over and over, “Stay down, or I’ll kill you.”

After Yara leaves, it takes Theon a long time to get back to the ocean, but when he does, it is the only place that will always welcome him, even in death. Just as a castle represents a permanent symbol of fortitude and harmony for the Starks, the sea is a place of promise for Theon that can never be burned or sacked. It does not discriminate against his Northern personality traits, any more than it offers him especial protections from its elements because he is the son of a king. In Season Seven, when he washes his own blood and the blood of his attacker off his face and simultaneously re-baptizes himself, Theon finds a similar sense of belonging in sea that Daenerys finds in the sand of the same beach, but he goes a step farther. Theon finds his own home, in himself as much as in the sea, and with it a sense of confidence and trust in himself that is equivalent to the unity that he achieved with Sansa in the frozen woods– a unity which is founded on the concept of home: stability, acceptance, and trust– rather than on a building itself.

Westeros’ families, or Houses, in all their discord or comraderie, are the beating heart of Game of Thrones, and at the heart of these families are there homes. While for many great Houses, these take on physical manifestations such as Winterfell, Dragonstone, the Dreadfort, or Casterly Rock, other homes are simply things that make characters feel strong or unified: crumbling castles in the snow, delinquent brotherhoods,splashes of saltwater. In the end, a home is not so much a castle, as a conviction. A recognition of what home means marks, rather than mere return, marks the finalization of a character. They have achieved harmony, whether with their larger family units or communities, or simply with themselves. They understand, if not where they come from, who they are and where they are going.

![[Book Review] The Blade Itself (The First Law Trilogy) by Joe Abercrombie](https://bendthekneegot.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/01/1516047103_maxresdefault-218x150.jpg)