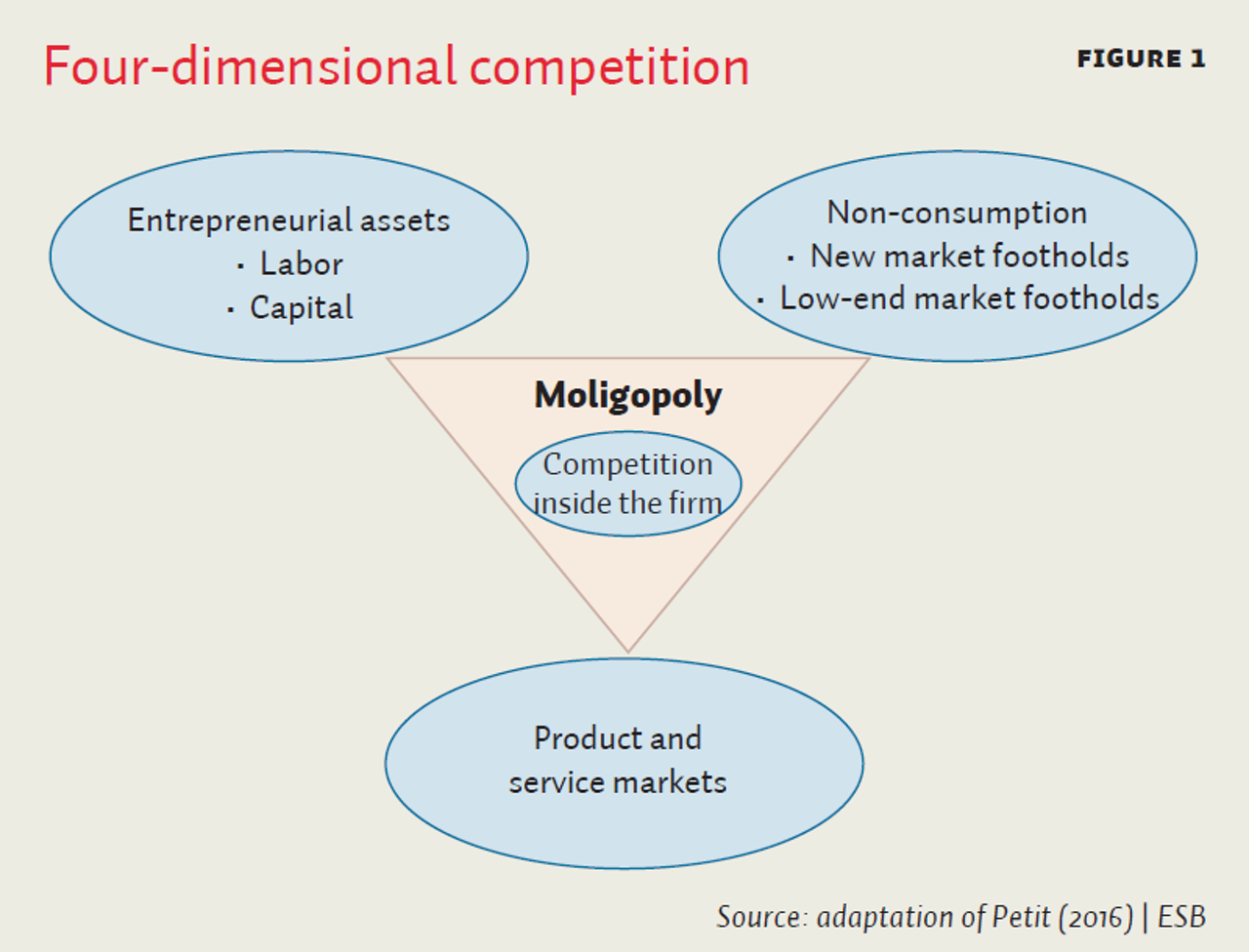

I’ve written previously about the research of competition scholar Nicolas Petit. In his 2016 paper, “Technology Giants, the Moligopoly Hypothesis and Holistic Competition: A Primer,” Petit the argues the Big Tech firms — while currently dominant in their core businesses — engage in considerable “holistic competition” with each other across a variety of industries and areas as they look for the next big thing and try to avoid disruption. A new paper from Petit illustrates it this way:

Petit also uses a fun Game of Thrones analogy to explain his approach:

Moligopoly competition is like Game of Thrones. In the long term, it is more akin to a survivalist game than to a profit-maximizing one, as Nobel Prize economist Armen Alchian once observed.

Moreover, the metaphor is particularly apt in the short term, because moligopolies operate like HBO’s Game of Thrones families: they compete with highly distinct capabilities and resources across various territories.

In digital Westeros, Apple is the Lannisters: it sits atop a mountain of cash, enjoys strong legacy products, and its internal processes are very secretive. Amazon is the Targaryen family. It is a big bazaar, host to many communities; it raises its army at a methodical pace; and it has a dragon’s ability to fly to any market: it scares every other tech player. Microsoft is the House of Stark of Winterfell: it’s become the good guy of big tech, to the point that it is out of the FAANG acronym. Like Ned and Rob Stark, Microsoft has paid a big price in the past: its monopoly was decapitated, leading to the departure of its two legendary CEOs Bill Gates and Steve Ballmer.

More seriously, the moligopoly theory can be used to cover other firms’ strategies than the FAANGs’, as long as they are competing four-dimensionally. In fact, statements by FAANGs regarding their possible competitors point to other possible moligopolists, like Cisco Systems, IBM, Intel, Qualcomm, Oracle, et cetera. At the same time, some FAANGs may not deserve to be called moligopolists if they essentially compete in substitute products and services, in which case established antitrust and regulatory policy can proceed at full speed.

I also conducted a long interview with Petit last September.

![[Book Review] The Blade Itself (The First Law Trilogy) by Joe Abercrombie](https://bendthekneegot.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/01/1516047103_maxresdefault-218x150.jpg)