HBO’s Game of Thrones isn’t afraid to break the hearts of its fans again and again, having slain vital characters—both loved and loathed—en masse throughout a seven-season tide of death and destruction.

With just one season to go and the dubious glory of the Iron Throne in sight for several players, the survival stakes couldn’t be higher.

Read more: ‘Game of Thrones’ just released another teaser. Here’s when to expect a full trailer

Researchers from the Australian Institute of Health Innovation at Sydney’s Macquarie University analysed deaths from the first seven seasons to tease out the stats behind the slaughter. Their results were published Sunday in the journal Injury Epidemiology.

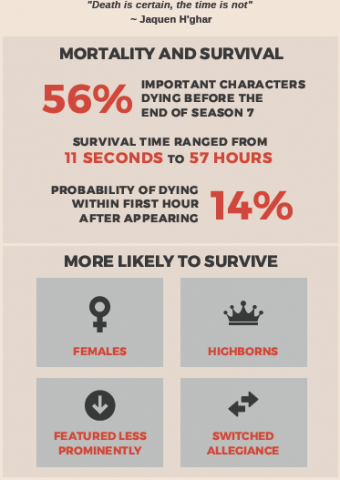

Taking 330 “important” characters into account, the study authors noted 56 percent have already been killed off. For new characters, there’s a 14 percent chance of dying within their first hour on the show. Most people die from injuries—often to the head and the neck—but burns and poison are also pretty popular.

Characteristics including female sex, high birth status and low prominence in the show were all linked to survival. Switching allegiance, although it may seem like a risky move, was also associated with longevity. In fact, disloyal characters were 65 percent more likely to survive.

Westeros—home to the Seven Kingdoms featured prominently in the series—saw far more deaths (80 percent) than its neighbor Essos.

“While these findings may not be surprising for regular viewers, we have identified several factors that may be associated with better or worse survival, which may help us to speculate about who will prevail in the final season,” author Reidar Lystad said in a statement.

If the past is anything to go by, the odds don’t seem great for characters that are male, prominent, low born, Westerosi or loyal to their faction.

But for a show as unpredictable as Game of Thrones, having the best survival charateristics doesn’t guarentee safe passage to the end of the series. Lystad doesn’t have a lot of hope for his favorite remaining character, Tyrion Lannister. “He likes to do research, read books and drink wine; that is something I can relate to.” Lystad told Newsweek. “Although he possesses some of the characteristics associated with better survival chances, I do not think he will make it all the way to the end.”

The research was limited by a number of factors. Excluding unimportant characters, for example, means hundreds of background deaths aren’t considered. Even estimating the total population of the realm is tough.

But the authors are reasonably confident about the accuracy of their data. In addition to cross-referencing internet databases, “independent data collection by two authors watching the DVD box set should have served to minimise errors.”

“For obvious reasons the world of Game of Thrones cannot be interpolated into human history,” the authors wrote. But it may be “instructive” to compare the violence, death and social structures found in real human history with those in the fictitious isles of Westeros and Essos.

“The political structure of the realm is evidently unstable. The legitimacy of the ruling power is questionable and the rule of law is ineffective,” the authors wrote. “Knowledge and reason do not appear to play a significant role in problem-solving and decision-making.”

The violence and chaos of author George R. R. Martin’s A Song of Ice and Fire books, on which the show is based, are loosely inspired by medieval Europe, and England’s real-life Wars of the Roses in particular.

Although the research doesn’t have any implications for the real world, Lystad told Newsweek, “It is an opportunity to reflect on our own current situation and how we ended up living in relative safety.

“The world of Game of Thrones can perhaps help remind us of our own violent past, of how far we have progressed.”

But even if it doesn’t, “it also seemed like a convenient excuse to re-watch the first seven seasons before to the final season hits television screens next year,” Lystad, an injury epidemiologist and prevention scientist, added.

Violence prevention clearly isn’t a priority in Game of Thrones, the authors wrote. For whoever finally wins the seat of the Seven Kingdoms, there’s plenty of scope for improvement.

But of course, as the citizens of Essos know well: valar morghulis—all men must die.

![[Book Review] The Blade Itself (The First Law Trilogy) by Joe Abercrombie](https://bendthekneegot.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/01/1516047103_maxresdefault-218x150.jpg)